February 24, 2016

The Story of Church Creek

Introduction

The Story

Church Creek is considered one of the most polluted tributaries of the South River. No small part of this is due to land use of the surrounding area.

Church Creek is considered one of the most polluted tributaries of the South River. No small part of this is due to land use of the surrounding area.

A watershed, or an area of land within which all water drains into one body, is normally made up of a combination of both natural and developed landscapes. Water from rain and melting snow can be absorbed by natural surfaces, like forest floors, gardens, or lawns. However, water that falls on harder, man-made surfaces, such as parking lots, asphalt, or roofing, will run off of these surfaces until it finds an area where it can be absorbed or reaches a water body. On its way, rainwater runoff picks up and carries with it many substances that can disrupt the aquatic ecosystem.

Some substances, such as pesticides, fertilizers, and oils are harmful even in small quantities. Others, such as sediment that has been washed away from bare soils on construction sites or farmland, pet waste, and grass clippings become harmful when a certain concentration is attained.

Believe it or not, sediment is actually the biggest and arguably the most harmful, pollutant for the South River. Not only can it directly impair the health of aquatic organisms, but it can also indirectly contribute to dead zones – areas unable to support significant aquatic life.

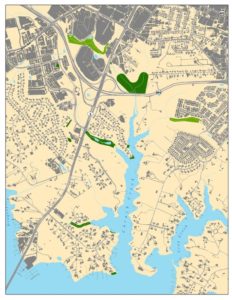

Most of Church Creek runs through Annapolis and a great deal of developed land. It is no surprise that Church Creek’s watershed is made up of around 55% man-made impervious surfaces. Scientists have determined that harmful effects on plants and wildlife populations occur when impervious surfaces make up 5% or more of the watershed. To see photos and learn more about the Church Creek Headwaters Site, click here.

While some environmental agencies identified this creek as a priority for restoration, others considered it too impaired for restoration efforts to be worthwhile.

South River Federation’s Role

Without intervention, the Federation would have been fighting to heal a river against insurmountable levels of pollution from the Church Creek watershed. This is comparable to attempting to provide physical therapy to someone who is still bleeding from an injury. One must first address the source of the problem before moving on to tend to any effects that the problem may have inflicted.

The South River Federation saw an opportunity to address a large source of pollution for the South River. By implementing a comprehensive restoration initiative along Church Creek that utilized cutting edge techniques to physically and biochemically filter runoff, aiming to reduce the pollutants gushing from the Creek into the South River. Although Church Creek itself may never support wildlife the way it once did, the Federation is confident that basic biological functions can be restored and the majority of pollution trapped or treated before reaching the river.

Church Creek Restoration: The Headwaters

One of South River Federation’s largest projects is located near the top of Church Creek, just off of Rt.665, Aris T. Allen Blvd. Characterized by steep ravines and deep, narrow stream channels, this area was highly eroded from years of poor stormwater management. Surges of stormwater runoff, made worse by the high percentage of impervious surfaces from the surrounding area, repeatedly ripped sediment away from stream banks and washed it, along with other pollutants, into the South River.

To restore this area, the Federation completely terraformed the ffive-acre site. Ravines were leveled and multiple small channels were joined to create a shallower and wider wetland area. In the event of a large storm, this enables the stream to spread across the entire flood plain, dramatically reducing the speed and force of the water. In this manner, the reconnected flood plain works to prevent erosion, thereby, limiting sediment pollution.

Large step pools were built as a tool to slow and filter water before it entered the South River. Water in this system slows and cools, filling one pool before cascading down into the next. Filtration occurs with the help of sand and mulch, which partially constitutes the form and subsurface of the pools. By driving water under and through these substrates, the wetland pools work to treat the water, similarly to the way a carbon filter in your Brita water pitcher removes particles and chemicals from your water.

Research indicates that the ideal and most effective location to install a restoration project is at the upper source streams of a creek. The Church Creek Headwaters site is located at a point where four streams converge halfway down the creek basin. Unfortunately, at the time when the Federation was searching for a location to install a restoration project, none of the shopping centers or apartment complexes stationed at the top of the source streams were interested in terraforming their properties.

It wasn’t until Jerry Blackwell, owner of the large property located just above Church Creek tidal waters, partnered with the Federation in 2007, that an opportunity to do a large scale project on the main stem of Church Creek arose. This site was to later become the aforementioned Church Creek Headwaters site (2014).

Blackwell spent an entire decade using tractors to pull cars, trailers, 55 gallon drums, trash bags and tires (lots of tires) out of the ravine.

Blackwell said that when he purchased the property and asked about the illegal dumping in the creek, the seller flipped his palms up and said, “Well, what’s done is done. Nobody cares about this creek anyway.”

In fact, after the formerly resistant commercial property owners at the headwaters of Church Creek saw a real-life, local example of the large scale in-stream restoration project, they changed their minds. The Federation just completed a project at Annapolis Harbour Center this past spring (2016) and is in the final stages of permitting for others near Allen Apartments and Bywater Mutual Homes.

Where Application Meets Policy

Despite receiving criticism concerning the mid-basin location of the Church Creek Headwaters project, the Federation pressed on with the initiative, knowing that the ideal conditions for a restoration project could take years to present themselves. Since the completion of this project, the Federation has installed numerous other large-scale projects.

With these multiple projects, the Federation has the unique opportunity to observe the effects of layered restoration. This allows stormwater runoff to be treated several times before reaching the South River. Current research indicates that this approach has the potential to exponentially improve the water quality and wildlife abundance.

Due to its size, location, as well as its concordance with other Church Creek projects, the Church Creek Headwaters restoration site is on the cutting edge of restoration projects. If the promising results that we have observed thus far progress into long term effects, this project could serve as a model for other streams with similar challenges throughout the country.

This Church Creek Headwaters Project is the center point for the Federation’s Church Creek restoration initiative, but the Federation has completed 13 other projects within this Creek’s watershed, including rain gardens, living shorelines, bioretention areas, and in-stream restoration. To see more Federation Restoration Projects, click here.

Results of Restoration

The Effectiveness of the Project/ Data Challenges

Determining the effectiveness of restoration is not as simple as comparing the animal, plant, and water quality surveys from before to after project installation. Because there are numerous factors influencing the outcome of these surveys at any given period of time, such as season, weather, and upstream happenings, a large amount data needs to be collected in order to account for environmental variation.

Determining the effectiveness of restoration is not as simple as comparing the animal, plant, and water quality surveys from before to after project installation. Because there are numerous factors influencing the outcome of these surveys at any given period of time, such as season, weather, and upstream happenings, a large amount data needs to be collected in order to account for environmental variation.

The Federation does not yet have enough data to make any definitive conclusions about biological or chemical trends. However, preliminary data may provide insight into how the stream is adjusting to the relatively new system.

Water Chemistry

One of the goals of Federation restoration projects is to lessen the impact of stormwater runoff on the stream ecosystem.

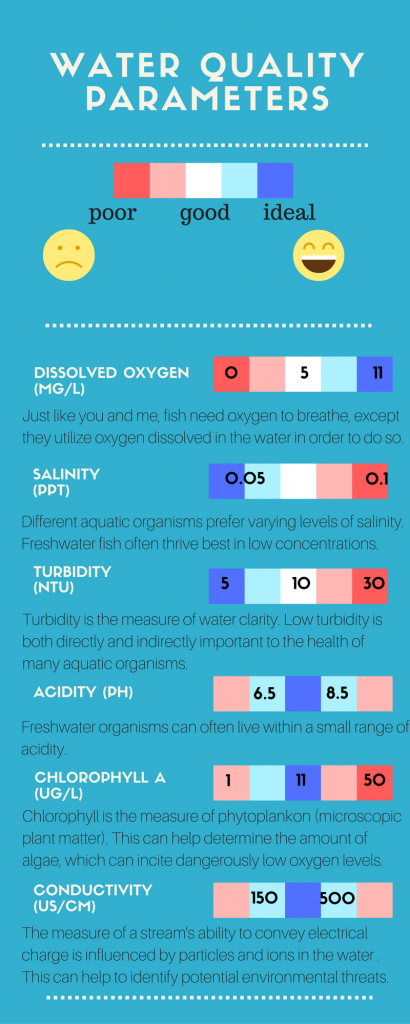

We hypothesize that because projects aim to slow rainwater surges with previously mentioned restoration techniques, runoff generated from storms will have less impact on the chemistry of the water and the well-being of the organisms living there.We think that this change may become increasingly evident as the restoration site matures and evolves into a more stable ecosystem. Some of the parameters measured to assess water quality include dissolved oxygen, acidity, conductivity, turbidity, salinity, and chlorophyll (for more information about these parameters, please refer to the diagram to the left).

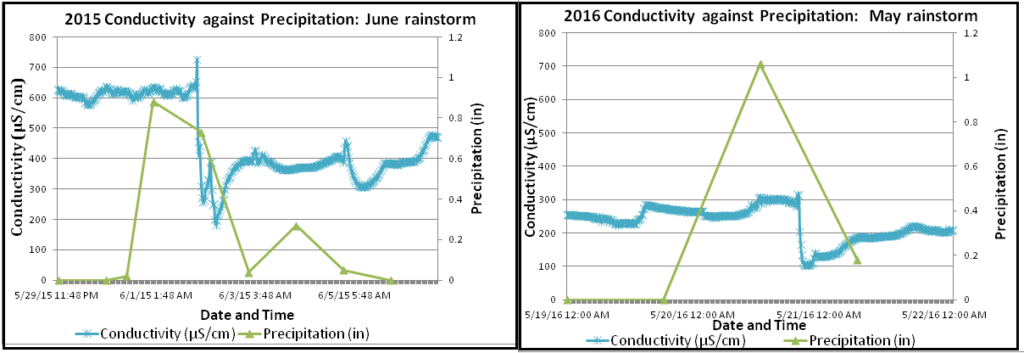

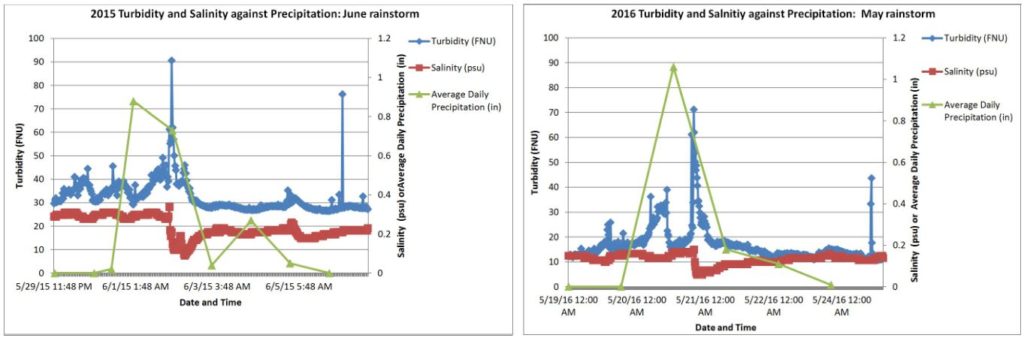

As a starting point, we looked at two similar rain events at the Church Creek Restoration site. The first took place in June of 2015 (1 year after restoration) and the second in May of 2016 (2 years after restoration). With each, the rainfall averaged between one and two inches. The 2016 storm seemed to have less of an impact on water quality than the 2015 storm.

During the height of the 2015 event, conductivity spiked more than twice as much as it did during the climax of the 2016 storm. Additionally, both turbidity and salinity at the peak of the 2015 storm reached values that were slightly more extreme than were observed in the 2016 storm. It is also worth noting that the average baselines for all of these parameters during the first storm seemed to be higher than the latter. Although further analysis is required, if it is the case that conductivity, turbidity, and salinity show a significant and consistent decline in each parameter’s average baseline, this could indicate the reduction in sediment pollution and the potential for a more productive ecosystem. Please refer to the graphs for a visual display of this data.

While this information seems to support the Federation’s hypothesis, it is impossible to draw any firm conclusions from looking only at these two different storms from varying years.

Nonetheless, we hope to continue seeing developments like this one as we delve into more data analysis.

Figures 1 and 2. Conductivity (μS/cm) was measured every 15 minutes with a continous monitoring Water Quality Sonde during these 2015 June and 2016 May rainstorms. Daily precipitation was averaged from the United States Naval Academy’s rain gauge station. Near the peak of precipitation (in) conductivity dropped 544.4 μS/cm in the 2015 storm and 208.1 μS/cm (less than half as much) in the 2016 storm.

Figure 3 and 4. Turbidity (FNU) and Salinity (psu) were measured every 15 minutes with a continous monitoring Water Quality Sonde during these 2015 June and 2016 May rainstorms. Daily precipitation was averaged from the United States Naval Academy’s rain gauge station. Around the same time that precipitation peaked in both storms, turbidity increased and salinity dropped. The 2015 storm exhibited readings of 90.75 FNU of turbidity and 0.09 psu of salinity and reached 71.34 FNU and 0.06 psu in the 2016 storm.

Biological Data

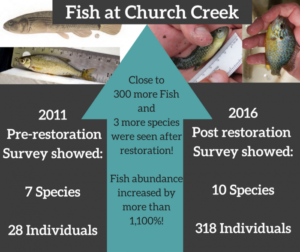

Another way to determine the effectiveness of a stream restoration project is through the observations of wildlife that inhabit the area. Through initial biological surveys at our Church Creek Headwaters restoration site, we have observed an impressive response from aquatic wildlife. Close to 300 more individual fish were found in the stream area after restoration than were found before restoration. Similarly, the number of individual amphibians found at the site rose over 500% between 2013 and 2015! This is especially exciting because it is unusual to see such a rebound so quickly after installation. (This project was only just completed 2 years ago in 2014.)

Another way to determine the effectiveness of a stream restoration project is through the observations of wildlife that inhabit the area. Through initial biological surveys at our Church Creek Headwaters restoration site, we have observed an impressive response from aquatic wildlife. Close to 300 more individual fish were found in the stream area after restoration than were found before restoration. Similarly, the number of individual amphibians found at the site rose over 500% between 2013 and 2015! This is especially exciting because it is unusual to see such a rebound so quickly after installation. (This project was only just completed 2 years ago in 2014.)

Restoration takes time

While we have seen promising results in preliminary data, it can take years before restoration projects start to show positive impacts on the ecosystem or stormwater runoff.

It has been 10 years since the completion of the Federation’s Wilelinor restoration site, located along another branch of Church Creek, and we are finally starting to see some significant responses downstream as shown by the photos below. The first, an aerial photo of the site, shows a clear plume of water leaving the project before it blends with the murkier water from another branch of the Creek. We believe that this may have resulted from decreased sediment discharge from the project area. Wilelinor uses a similar type of step pool conveyance system to slow and filter water as the Church Creek Headwaters site.

It has been 10 years since the completion of the Federation’s Wilelinor restoration site, located along another branch of Church Creek, and we are finally starting to see some significant responses downstream as shown by the photos below. The first, an aerial photo of the site, shows a clear plume of water leaving the project before it blends with the murkier water from another branch of the Creek. We believe that this may have resulted from decreased sediment discharge from the project area. Wilelinor uses a similar type of step pool conveyance system to slow and filter water as the Church Creek Headwaters site.

The fish in the next photo is the chain pickerel. This is an apex predatory fish, meaning that it sits near the top of its food chain and can only live sustainably in an area that has a varied and stable food web. The chain pickerel had not been seen in this branch of Church Creek for decades until just recently in both 2015 and 2016 biological surveys. Its presence indicates a developed and relatively stable ecosystem. In other words, restoration looks to be working!

I hope you enjoyed this capstone project! I could not have put it together without the help of all the extremely supportive South River Federation staff.

Stay tuned as the Federation uncovers more information about the Church Creek Headwaters site near Rt. 665, Aris T Allen Blvd. Data analysis is underway!

Cheers,

Sarah Giordano, Chesapeake Conservation Corps Volunteer ’16

See more blog posts about this project here.